As I watch and lament the current war in the Mideast, as I wonder what I can do about the threats Israel faces and the deaths facing hundreds of thousands displaced Gazans, I also am reading a history of the Jewish Labor Bund. Its warning about the future that we have now reached is worth repeating.

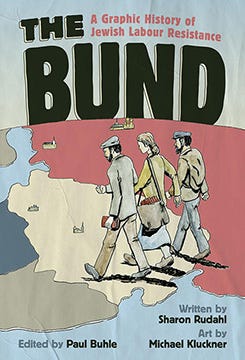

My interest in the Bund and its predictions began when I read the delightful illustrated graphic history book, The Bund: A Graphic History of Jewish Labour Resistance, written by Sharon Rudahl, illustrated by Michael Kluckner, and edited, with a great introduction, by Paul Buhle.

As this beautifully illustrated book — and other commendable earlier volumes on the Bund by Jack Jacobs, Frank Wolf, and David Slucki — will tell you, the Jewish Labor Bund began in 1897 in Russian-occupied Vilna, Lithuania. Initially meeting illegally, its founders resisted tsarist oppression and bans on unions through underground publications and calls for resistance. While the Yiddish-speaking Bundists favored socialist programs, they broke away from Lenin and his Bolshevik Party in 1903, and ceased to exist as a Russian political party in the 1920s.

The Bund found greater support in other countries, particularly in Poland between world wars, where it thrived with its own schools, health clinics, cultural programs, elected representatives, and self-defense units. Before one exemplary Bundist, Bernard Goldstein, became the leader of a self-defense unit in Poland, he survived Russian imprisonment in Siberia. Later he worked with the Polish underground resisting fascism in World War II, participated in the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, and ended up living in the United States.

Goldstein’s activism and resistance to fascism exemplify a practice the Bundists termed doykayt, which translates from Yiddish into “hereness.” Bundists like Bernard Goldstein and Pati Kremer (both are given special attention in the new graphic history) struggled for human rights and resisted oppression here and now, wherever they lived. They didn’t have to seek a Zionist homeland in Palestine when they could fight for peace and freedom in Eastern Europe or (if they migrated, as many other Bundists did) in the Americas, France, the UK, and Australia.

Doykayt still offers a viable alternative to Zionism, and its practice can be detected in the American actions of If Not Now and Jewish Voice for Peace, groups currently calling for a ceasefire in Gaza and for an end to the occupation. (Naomi Klein in her book Doppelganger sees these two groups as descendants of the Jewish Labor Bund.)

After heroic resistance in the Warsaw Ghetto and in partisan militias during World War II, the Jewish Labor Bund survived as an organization, but many of its members did not. War and death camps destroyed its European base. Through transnational migration, however, Bundist approaches to culture and politics continued to influence programs elsewhere, notably in American branches of the Arbeter Ring/Workers Circle and the Australian branch of the Jewish Labor Bund, which survives in Melbourne. A Bundist-like commitment to socialism can be seen in Democratic Socialists of America, although Jewish and Yiddish-speaking backgrounds have been assimilated into a more diverse collection of American socialists. (Some members of DSA’s predecessor organizations were actually Bundists.)

It’s good news that groups of socialists and Jewish activists have taken on struggles that the Jewish Labor Bund initiated. The practice of doykayt, combined with socialist community-building and the culture and literature of yidishkayt (Jewishness) that enveloped the Bund’s work, remain inspiring, and may help some of us address current crises in Gaza, Israel, and America.

I was born too late to join the historic Bund projects in Poland, but not too late to reconsider some of their proposals for doykayt and for peace in the Middle East. One statement on Palestine issued by surviving Bundists who met at an international conference in 1948 resolved that the “Palestine question can only be solved on a basis of democracy and justice," and that (in David Slucki's paraphrase in his book on the Bund), “freedom and equal rights for all the inhabitants of the land was the only solution. A government of the minority (Jews) over the majority (Arabs) was not an option, and cooperation was the key to ensuring security for Jews in Palestine; therefore, Zionist goals of a separate Jewish state needed to be abandoned. The resolution called for independence of Palestine, with recognition of the local Jewish population as equally invested stakeholders in governing the country. A Jewish state …could only lead to perpetual war with the local Arab population and the surrounding Arab states."

The Bund’s advocacy of a federation that would allow Arabs and Jews national and cultural autonomy within the same territory was not accepted by the powers that ruled the region in 1948, and probably won’t be accepted now. But the 1948 prediction of continuous war as the alternative to coexistence seems all too prophetic today. Could some variation of the Bund’s plan for a shared state ever have been implemented? Since Prime Minister Netanyahu has vociferously rejected a two-state solution, might the Bund’s one-state solution be the only post-war alternative? To explore these questions further, I recommend that the uninitiated start by reading The Bund (available from AK Press in the USA), then go on to other books that discuss the Bund’s history and practices. At the very least you will know more about what has been lost, possibly what can be recovered from the Bund’s achievements in Yiddish culture, socialism and anti-fascism.

It turns out it is not too late to become a member of the Bund. The branch that survives in Melbourne, Australia, accepts international members. As a member of the Arbeter Ring/Workers Circle of Northern California, I see myself as a Bundist descendant already. But I also welcome the Melbourne Bund’s position on some issues, notably one recent statement on the Gaza war that almost could have been issued by the Bund in 1948: "Israel must articulate a path towards a just, lasting, and secure future for Israelis and Palestinians alike based on the principle that all people in Israel, Gaza, and the West Bank have a right to self-determination and freedom from oppression and violence."

Even without joining the Bund, it’s possible to practice doykayt and struggle for justice here, now, wherever we are.

_____________________

Joel Schechter is the author of Messiahs of 1933: How American Yiddish Theatre Survived Adversity through Satire and The Pickle Clowns: New American Circus Comedy, among other books. Joel is emeritus professor of theatre and dance at San Francisco State University.