As we neared disembarkation in Vancouver, BC, I had to admit that I had found cruising in Alaska for ten days to be a bit stupefying. Even our shore excursions were filled with ease, comfort and hand-holding. When we canoed to the Davison Glacier in Skagway, for example, the ten-person canoe had an outboard motor that our guide put into action after about six paddle strokes. The most exciting part of that day was encountering the various young women who were our guides, all recent college graduates full of outdoor competence and bubbling enthusiasm for our planet. Most of the “Alaskans” we met over the course of two weeks were, in fact, young people working summer jobs who hailed from California, Tennessee, Ohio, etc.

By contrast, the great majority of passengers on our ship were old, and bite-sized experiences may have been for them just what the doctor ordered. There was nothing challenging in the cruising experience, nothing more complicated than choosing which dishes to enjoy for dinner and which clothes to wear for warmth as we walked around the towns of southern Alaska: Homer, Hoonah, Skagway, Juneau, Kodiak, Ketchikan, most of them a balmy 53º or so, with fishing- and tourist-dependent populations of about 3,000 souls apiece. (Hoonah claimed to have three times as many bears as humans.)

Now, if I ran a cruise line, I’d include an art room, a music room, and other real estate to encourage passenger interaction and expressive creativity. Being pampered like a faux billionaire for two weeks, with no opportunity for giving as well as receiving, really had begun to bloat my soul.

Even watching the ocean and the mountains that line Alaska’s inner passageway (the marine highway, typically just a few miles across) eventually became familiar — as did the dozens of amazing totem poles and museum placards created by the 10,000-year old indigenous peoples of southern Alaska. Clearly there has been a powerful revival of indigenous culture in the state, and I ruminated quite a bit on the contrast between the rootless individualism of our modern capitalist culture, which gives rise to constant creative experimentation but a real lack of communal connectedness, and the highly communal, highly traditional culture of the native people of Alaska, which seems to produce very repetitive artistic symbolism and strict generation-to-generation behavioral codes.

So I’ve now flown over snowcapped mountains in a helicopter and felt the tug of eight mushing Alaskan huskies on a snow sled as we raced across a snow-covered glacier. I’ve seen sea otters floating on beds of kelp, sea lions barking and groaning on their boulders, bald eagles diving for food, and grey whales spouting and diving. Encountering wildlife in the actual wild is always, for me, a revelatory experience, as I am thrilled by the sophisticated design of our wonderful planet’s creatures.

And I’ve contemplated, thanks to John McPhee, what life was like for indigenous Alaskans and for the crazy men and women who migrated there in the mid-20th century and led lives of subsistence and hardship and ultra-independence. I would’ve starved by week 2.

At the end, we spent two days in Vancouver, BC, a city of 600,000 with great bike paths, clunky glass buildings, lots of drug-addicted street people, and many, many immigrants speaking many, many languages. It then took 24 hours to get home because of airline delays (five gate changes for a single flight!) — and Susan is now laid up with Covid while I’m busy mowing my overgrown acre-and-a-half (such a pioneer!), squishing the spongy moth caterpillars that are devouring our oak trees and rose bushes, and feeling like I’m never again going anywhere to which I can’t drive.

Unless I can scrape it together, someday, to go to Hawaii . . .

___________

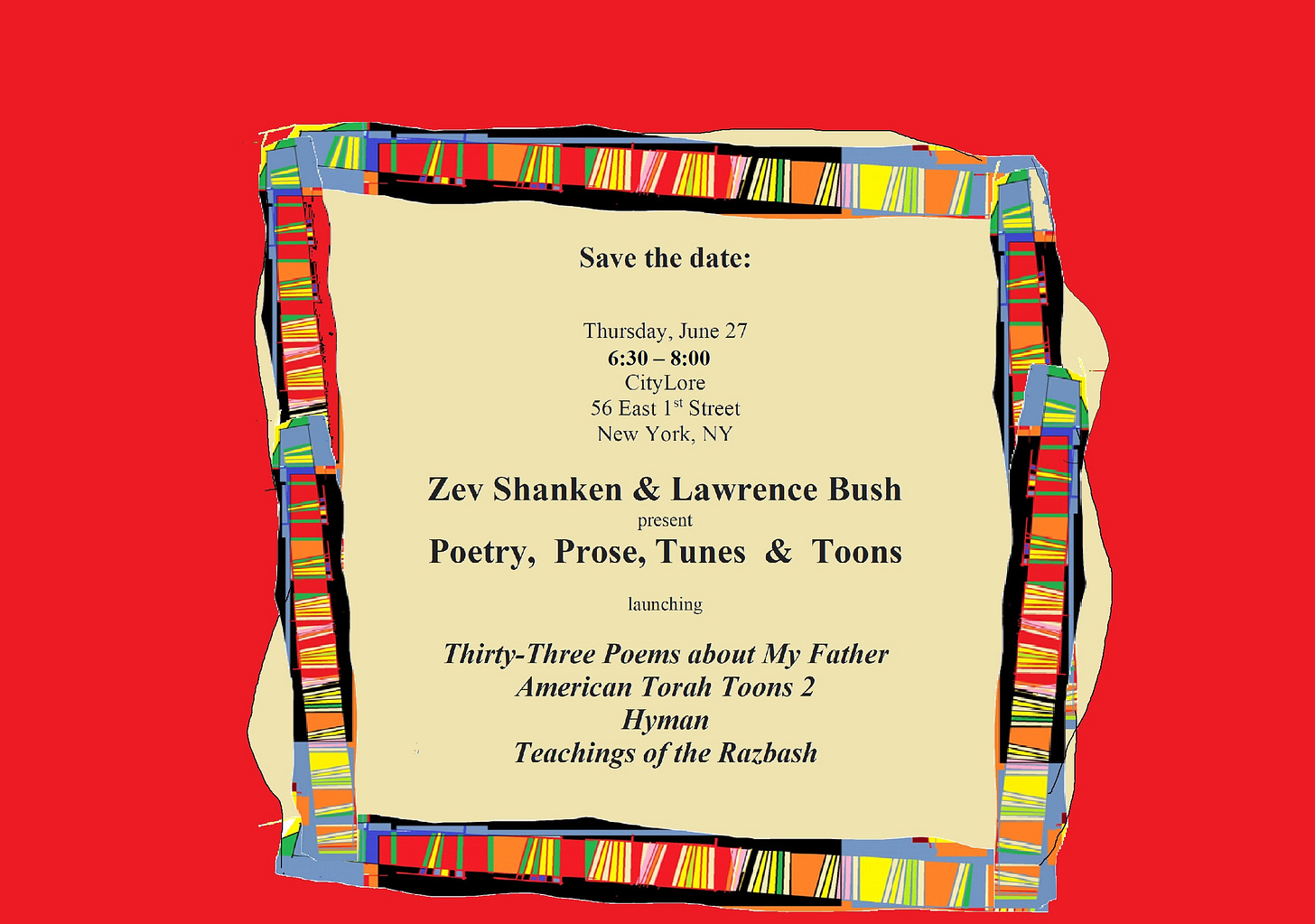

To friends in the New York area:

Good point about individualism vs. traditional tribal loyalty. Welcome back. Much to ponder and write. Looking forward.

Welcome home Larry and Susan; glad you are safely home, we've missed you.